Everything you've always wanted to know about Maturity Models...

...but were afraid to ask

We might as well debate how many angels can dance on the head of a pin as argue the merits of the SAFe Maturity Model; the principles are beyond reproach, but in practice it is often brought down to level of a “best practices” sales catalog. Agile has been reduced to a commodity that consultancies sell to enterprise, with the maturity model serving as a marketing tool created to provide a consistent buyer’s path.

An alternative with merit is the Kanban Maturity Model which stands on the ground of improved productivity as measured by mathematically unambiguous key indicators of productivity.

Barry O’Rielly recently penned a post “Why Maturity Models Don’t Work”. Other than the fact that he omitted the Kanban Maturity Model altogether, I agree with Barry’s thesis, every point, in detail .

While maturity models have been held in high regard for years as proven templates for continuous improvement, it’s becoming quite evident that their structure is actually their greatest flaw—far too static, a snapshot, a single perspective and a solution path unable to keep up with an ever-changing world.

— Barry O’Reilly

Before we put the KMM in light of Barry’s laudable dressing-down of Maturity Models, let’s put it in the context of some of the more fashionable models.

The CMM is the Mother of Maturity Models, whose good intentions were perverted by DoD funders who bent the process to their purpose of classifying vendors through assessment, a static objective by design.

Applying a static model like a Maturity Model to dynamic variables — such as markets, customer needs and technology — rarely meets expectations

— Barry O’Reilly

Many good people have worked to breathe purpose into CMM, and it has helped some organizations to lay a roadmap out of chaos, but the backward-looking assessment mode is in its DNA.

The children of the CMM such as the Digital Transformation and SAFe Maturity Models were schooled from their tender years to serve as marketing tools of the big consulting firms. They know no better.

After all, the vast majority of maturity models are sales tools created to market a consistent buyer’s path…

— Barry O’Reilly

Consider this nugget of wisdom from ” Assessing the adoption level of scaled agile development: a maturity model for Scaled Agile Framework”:

A maturity model is a structured collection of agile and SAFe practices, including the dependencies between these practices, would help organizations in defining a roadmap for agile/SAFe adoption. In order to identify a prioritized roadmap for SAFe adoption, it is important to understand which practices the organization currently performs well, and which practices it does not. It is critical to periodically assess the extent by which these practices are successfully adopted and can be improved. A maturity model acts as a basis for such assessments.

The SAFe Maturity Model inherits the CMM’s crippling feature of assessment as an outcome, but what’s worse is that the measure of success is stated in terms of practice adoption.

Practice adoption is a crappy metric because companies don’t sell Agile practices to their customers, they sell goods and services.

Oh … Wait! … consulting firms are in the business of selling Agile practices: it’s their inventory! No wonder why they need Maturity Models to hawk their stockpile of “best practices”.

To understand the pernicious implications of this, let’s take a look at the Maturity Model the Barry didn’t mention: the Kanban Maturity Model.

Often what people don’t say or leave out, tells the real story.

— Shannon L. Alder

Like other Maturity Models, the KMM helps guide in practice adoption but with the critical distinction is that practice adoption is not a measure of success.

The only real measure of success of an organization utilizing the KMM should be productivity. Many technology managers use the word “productivity” rather loosely; often they really mean local optimizations along the lines of keeping everyone busy, or perhaps they want to emphasize the importance of deadlines by equating productivity with performing according to a GANTT chart. Rarely do we find the word productivity used in a context that is accompanied by “..as measured by…” or anything remotely in the direction of specificity.

Every situation, no matter how complex it initially looks, is exceedingly simple.

— Eliyahu Goldratt

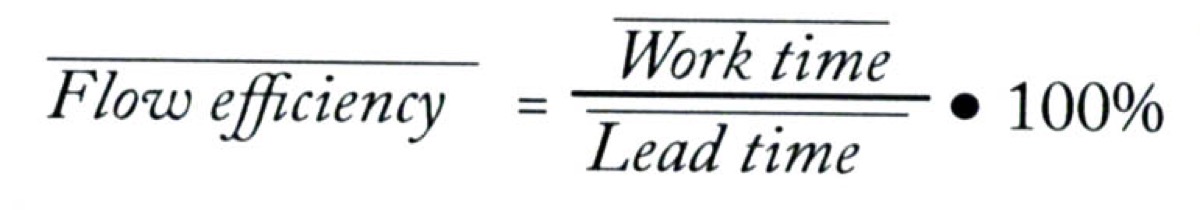

Kanban measures productivity in terms of throughput, and throughput can be measured rather precisely using Little’s Law:

L = λW

We can argue about the meaning of productivity in terms of additional measurements of the business value of delivered work, but as Eliyahu Goldratt pointed out in his critique of the Balanced Scorecard, there is a virtue in simplicity. Throughput doesn’t answer all our questions about business value, but it is a sufficient metric for the context of evaluating the relationship of practices with productivity.

The purpose of the KMM is productivity, not the periodic classification of an organization’s maturity level through assessment and it is not to measure the rate of successful adoption of practices. The objective of the KMM is the iterative improvement of throughput of the system, subject to unambiguous, measurable key results. That’s what makes the KMM the breakout Maturity Model, the first child of CMM to offer objective, evidence-based guidance to improved productivity.

The KMM is informed by numerous case studies that one can review, but the underlying strength is the clear-cut measurement of productivity; the feature which addresses what Barry O’Reilly rightly attacks as the lack of scientific process in Maturity Models. The choice of practice adoption is a hypothesis, the efficacy of which is subject to evidence. Little’s Law provides a simple to comprehend yet rigorous proof.

The reliance on a straight-forward productivity metric also addresses what Barry O’Reilly refers to the “filter bubble” problem of Maturity Models: that you only see what you want to see. You can put on your blinders if you want, but you won’t be able to hide the consequence of your preferences from the throughput metric.

Barry cites a similar problem of Maturity Models as a focus on only one person’s experience, opinion, or narrative of what is ‘better’. Gaming the narrative is unlikely to align with productivity improvements, so again, Little’s Law leaves little room for people trying to use the model to hide their agenda.

There are good practices in context, but there are no best practices.

— Cem Kaner

In other models, you’re good to go on to the next level when you’ve adopted the proscribed best practices, but the KMM isn’t like a video game where you advance to the next level by slaying imaginary dragons. You might think of it in terms of the Deming cycle: use the model to Plan, Do the practices that apply to your circumstances, Check the outcome in terms of throughput, and then Act on what you learn. In the KMM, the Check phase is rooted in a mathematically sound evaluation of key results.

Barry’s valid criticism that “how a company moves through each stage is completely arbitrary” is addressed in the KMM first by classifying phases as transitional vs consolidation, and then by favoring normative changes in transitional phases, limiting structural changes as much as possible to consolidation phases.

A normative change is a revision of policy or procedure which doesn’t disrupt social structure, thus is less likely to meet resistance and more likely to build trust in the idea that change can lead to improvement. A structural change may require some adaptation to roles, responsibilities or status of team members, hence less likely to succeed without the buy-in from those who are affected. Buy-in is earned by building trust.

The model proposes normative vs structural classification of practices by ascribing them to either transitional or consolidation phases, but recognizes that a given practice might represent a normative change in one organization while being a structural change in another. The important part is not that you respect the classification, but that you follow the principles.

A keystone principle of Kanban is start from where you are. Unlike other Maturity Models, the KMM has no presumption that intervention is somehow good. You start by visualizing the work, to help insure you understand what’s actually going on; then you limit the work in progress in order to drive the constraints to the surface. Only then do you consider changes to practices, and only then as a response to the problems you actually have. The model helps in making appropriate choices.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks about the need for "…a systematic protocol to determine when to intervene and when to leave systems alone." The KMM doesn’t insist on piling on practices but rather provides meaningful guidance on how a company might move through each stage.

Hopefully this dispels any illusions that the KMM is somehow about awarding maturity level merit badges. The key is to see it as a playbook in the game of continually improving productivity.

Happy is he who can trace effects to their causes

— Virgil

David Hofmann — "Angel Dance"

Let's agree to define productivity in terms of throughput. We can debate the meaning of productivity in terms of additional measurements of the business value of delivered work, but as Eliyahu Goldratt pointed out in his critique of the Balanced Scorecard, there is a virtue in simplicity. Throughput doesn’t answer all our questions about business value, but it is a sufficient metric for the context of evaluating the relationship of practices with productivity.